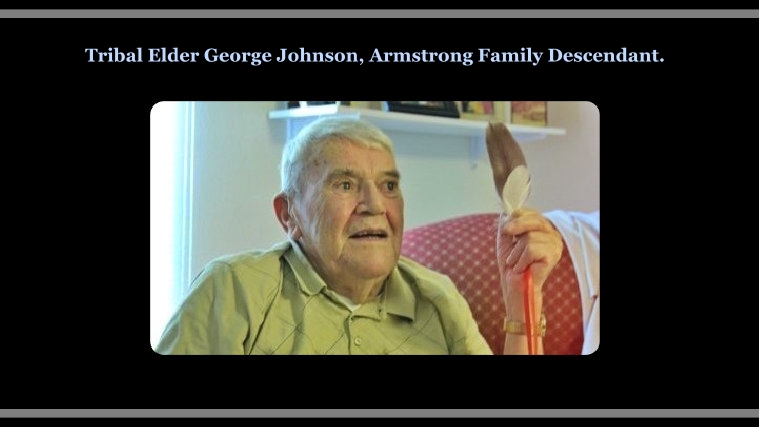

Honoring Our Tribal Elders: Shoalwater Bay Tribal Elder George Johnson, 1918-2013.

Written by Misty Shipman (from an audio interview by V. Keven Shipman).

Birth date: May 26th, 1918.

Birthplace: Raymond, Washington.

Favorite Color: Green. “I like the green trees and the green grass.”

How many siblings: 3 brothers and 1 sister.

Wisdom for the Children: Be good to the mothers and fathers. Stay out of trouble. Stay away from the dope and even stay away from the cigarettes. And the alcohol and all that. Grow up, and go to school, and go to college if you can, and make something of yourselves. Work hard.

On a sunny morning in late October, Keven Shipman and Brandt Ellingburg made the drive from the Shoalwater Bay Reservation in Tokeland, Washington, to Salem, Oregon, to visit an esteemed Tribal Elder. At the age of ninety-three, George Johnson is our oldest Tribal Elder, and he has a wealth of beautiful stories and memories from the early days of our Tribe, back before we were widely known formally as a reservation. The Kopa Tilikum team would like to thank Georgia and Chad Fryback for making the interview possible, and George Johnson himself for being willing to share his stories with us to be preserved for future generations.

Though I was able to speak with him on the phone beforehand, I could not be at the interview itself. Despite this, even listening to George Johnson’s voice carried a certain resonance and power. I felt endeared to him immediately. He spoke with a certain grace and passion. “Sharp as a rock,” as Keven described him, and full of memories of our sacred ancestors.

“Shipman, huh?” George said when Keven introduced himself. “Last time I was with a Shipman was when I was in Seattle to go into the service in World War II.” George ended up being deferred, because at that time he was working in a logging camp, and the government deferred loggers and climbers because the athletic workers were hard to find.

George remembers the logging camp being in Tokeland from the time he was a small child. For much of the year, George resided in South Bend, but he and his brother lived out on the Bay during the summer times, in a tent. “For a tent in those days, we’d just pitch some stakes in the ground, and throw a canvas over it. They didn’t have tents like they do now, not near. We called that our home, you know. We lived outside most all summers.”

Raised

by a single mother and older siblings, George spent most of his life

as an independent “free range” child, exploring Shoalwater Bay

land, working, and having fun.

“Wasn’t a lot of people around,

or cars. We was kids then. All we did was play. We brought ourselves

up.”

George’s “free range” life on the Bay happened partly as a result of being so far away from South Bend, but it was also due to his father’s passing. “My dad worked on a tug boat on Willapa Bay, hauling logs out of the Cedar River for Casey’s Mill Company. He went to sleep on the trip back home after towing rafting logs. Went to sleep on the bunk and his partner was driving and he rolled off the bunk. Breathed all that gasoline and oil.”

“Poison,” Brandt said.

“By the time he got home, he was gone. I was four years old.”

Life became much more difficult for his family during this time. George spoke about his mother with great admiration as he related her background and struggles. “My mother was the Indian part. She was Ben Armstrong’s oldest daughter.”

The survival of his family depended on everyone working together. The single-parent family of young children survived by taking odd jobs to feed and clothe themselves. The Shoalwater Bay land allotment provided George’s siblings with opportunity. As a result, summers were often spent visiting extended family members who made their homes on the Bay. As George spoke about these times it was hard not to get the powerful feeling that some of his best memories came from this formative time in his life.

“I would imagine you travelled by water?” Keven asked in order to discover exactly how George and his siblings reached the Shoalwater Bay from South Bend.

“Oh yeah, yeah,” George replied. “We went from South Bend to Tokeland on the Independence Ferry. There was no highway like there is today. When I was going to the reservation, we had to go from Chehalis to South Bend, then to Olympia, then to Westport. Finally we stopped at Georgetown. It took about a good day to get there in those days. That was in the mid-thirties.

We travelled by boat, mostly. We learned how to row pretty good when we were kids. After I grew a few years older, my brother and I would row from South Bend down to the Georgetown Sleugh, we called it, and make a camp and pitch a tent, and peel bark. We’d make about fifty cents a day, then.

We saw canoes, but they were pretty much gone when we were kids. We heard stories about them, but they had the rowboats when we were there. Skiffs, like we called them. Skiffs.”

George had other fond memories of those days, some about the sweet fruits he and his siblings would acquire, such as the choke-berries from the graveyard. “Chalk-berries, we called them,” he said reminiscently. There were other fruits the children loved, too, like plums and bananas.

“I can remember Roland Charley had a big plum tree out in his yard, and when we were kids we’d go, and plums would be ripe, and they’d drop on the ground, and they’d spread open, and the yellow jackets would just swarm in on them. And Anita would brush the yellow jackets away and they didn’t sting us, and we’d eat those green plums. They were so good, sweet, I can remember that, oh boy.”

George said he was between seven and eight years old when they ate the plums.

Being young in those days came with hardships, but it also came with special privileges. George was able to meet Chief Charley. “I remember going to see Chief Charley, and he was on his deathbed. He had a bunk bed built on a wall. He was laying on the bunk bed. And they had a fish stew cooking on the stove,” he recalled.

George had other fond memories from that time in his life. “We went out and swum across from where you go into the meeting room. The tide would come in over that warm sand, and the water would get in that, and there was a big pool, like a big pool, and we’d swim, oh, it was the best time, I’ll remember that always.”

George had other stories he wanted to share, treasured memories from his youth and adolescence.

“I heard you fellas were coming to see me. So I tried to remember some of the things that happened. Well, one thing happened, my father had a logging camp, and he had a cook house and a bunk house. My sister was a flunkie down there then. Helped do the dishes, pick up, and serve the loggers–you know and all that. Well, my grandmother was very close. She was very tight. And she had a bunch of bananas there on the table. And my sister said to herself, I’m gonna get a couple of those bananas and take them to the logging camp in the morning. So she took those bananas, and she took two bananas, and they wore long stockings there. So she put one banana down one leg, and one banana down the other. So, she walked out, and she said, ‘Come on George, we’re going to go over the hill,’ and she pulled up her dress and pulled down her stockings, and she said, George, I’ve got a banana for ya. She never did say whether her grandmother missed the banana or not. In those days, that was like ice cream or something, you know.

And I

remember Dexter. He was our best friend. We’d get a nickel or

something and go down there, and he’d have all that soda pop piled

in a soda pop cart that they had in those days, and he’d have them

piled up against the wall there. And he’d have strawberry and grape

and lemon lime, and root beer and all those flavors. And it’d take

us an hour to pick out just the one. And it was warm, too, you know,

but that didn’t matter to us. They had no

refrigeration then.

And he had a candy counter there. We’d look at that candy and just

look at it.”

“What did you do as a teenager?” Keven asked in order to gain a better understanding of this time in George’s life.

“My brother and I would still row to North river, Smith river, camp out and cut and peel bark. Even when we were teenagers. Make a little money to buy school clothes, ‘cause we didn’t have nothing.”

George explained that he and his siblings went to school in South Bend with around a hundred and fifty other students from grades six through twelve. They had some bad experiences in school which drew partially from the fact that they were impoverished.

“We did everything we could do. Pick berries, you know. Lots of those evergreen berries around there. There was a camp where we brought our berries. We might make a dollar a day, maybe, if we had a good day. And we’d work hard the whole day. But maybe that would help buy a pair of shoes, or a shirt.

The other kids would have nice clothes, you know, and we weren’t ashamed of our clothes. One thing my mother said, ‘Don’t be ashamed of your clothes.’ Lots of patches on them. My mother would sew patches on patches. But she said don’t be ashamed, and we never were.”

Though economic impoverishment may have contributed to the Johnson’s feeling like outsiders in school, it occurred mostly because they were Indians. “We had some racial problems, you know. We were the last to go on a party with the school kids, the last in line, last chosen for a ball game. The last chosen for anything. It wasn’t good.” George explained that his school comrades began to value his siblings when they got older, “because they were the best players on the team in baseball and football.”

“So, excelling in sports told them, hey, maybe we should rethink this thing,” Keven said.

George said that yes, it did partially help, but the racism was hard for his brothers, sisters, and mother. “She would have talks to help feel better,” George told us. “‘Just don’t get fighting with anybody over it. Stay cool as much as you can.’ She encouraged us to just mind our own business.” She also said that they should try to excel as much as they could in school and sports.

“Were your brothers and sisters good at school, or saw it as something they should do?” Keven asked.

“Well, we were so poor that my oldest brother had to quit school, and earn a little money to take care of my family. He was taught how to weld.” George’s brother ended up going to Oregon to weld, and would send home money to George’s mother to help take care of them. “My older sister was the same way. Five years older than I, but after she got old enough she would help my mother clean houses for these rich people. They made a sacrifice. I was the only one who graduated from high school out of the whole family.

My oldest daughter, Gail, was the first to go to college. Gail is 73 now. My second daughter was the second to go to college. That’s Georgia. She went to Southern Oregon school and learned how to be a teacher, and she taught school for quite awhile. Several years. And she married Tom Fryback. And my boy went to school and he did really good in school, and he got his doctorate degree. He’s the one who lives in Silverton. He comes and sees me all the time. He’s got a nice home over there. He and his wife have two boys, and one of them is a head chef at a big restaurant in Seattle.”

“A very successful generation,” Keven said.

George, Keven, and Brandt shared a smile. They ended the interview by presenting a gift to George Johnson, crafted by my mother Lory Ellingburg, to honor him. Brandt and Keven thanked him for spending time with them and sharing his life. Such stories from revered Tribal Elders are the heartbeat of the people, the lifeblood of the Tribe. We love to hear our Elder’s stories because they are filled with wisdom from our past.